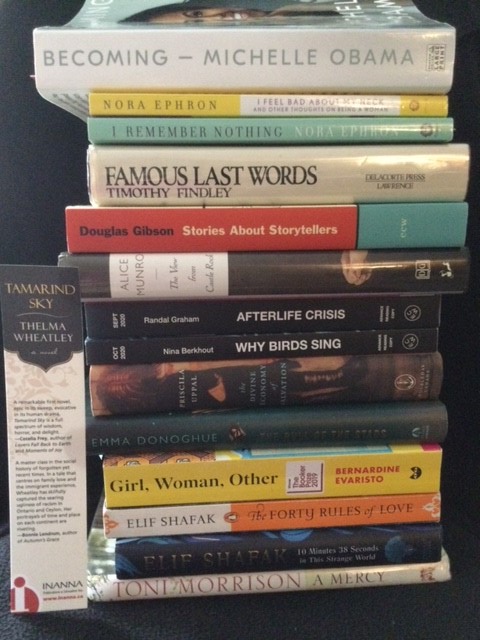

I’m coming to this blog with a feeling of guilt. I had intended to comment on many more books. But one day in an effort to create order on my desk and space in my head, I shelved every single book in the growing tower. Then I started a new pile.

Writing time has been compromised since Autumn 2021. It seems that “Urgent/Important” activities have taken precedence over “Not Urgent/Important” creative writing. (If you need a refresher on Stephen Covey’s time management quadrants, here’s a link: Stephen Covey Time Management Quadrant – Bing images ). However, I’m pleased to report that I’m finishing edits on my second manuscript and am steeling myself to let it go. It should be a simple process, but it’s not. I’m paralyzed by it. But enough about me. Let’s talk books.

If I followed my own advice and made notes as I read or wrote a summary immediately after reading, my comments would be fuller. I apologize for the brevity, which is why I’ve re-titled the blog from An Avid Reader Reviews to An Avid Reader Comments.

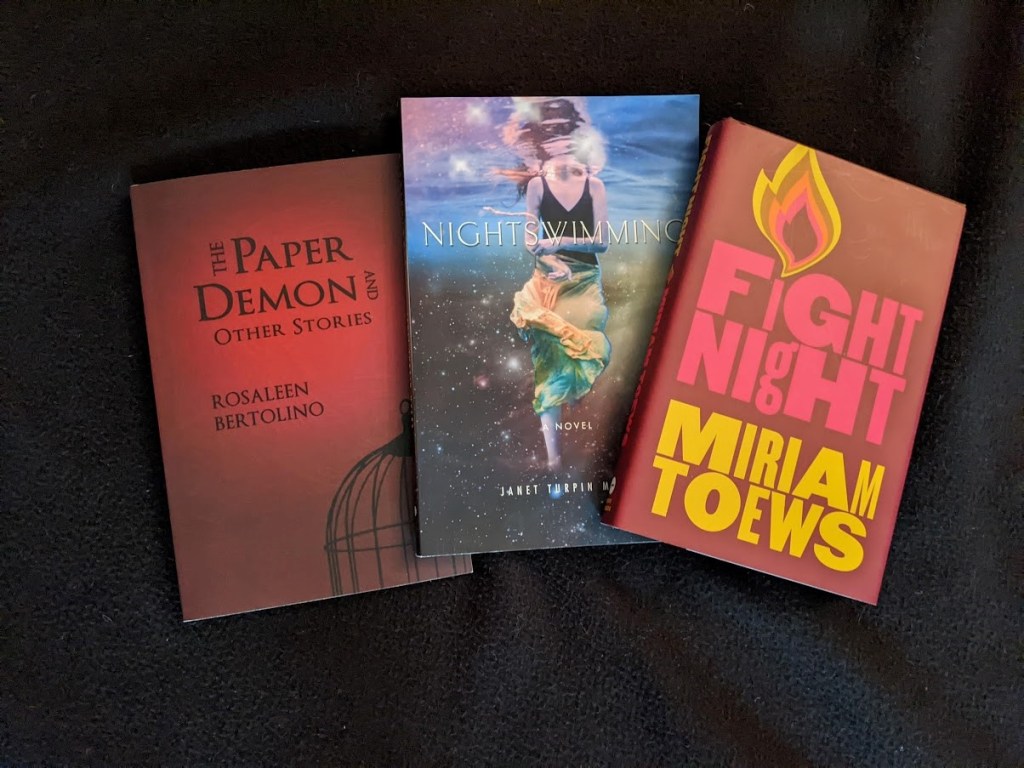

Paper Demon by Rosaleen Bertolino

I met Rosaleen Bertolino at the San Miguel Writers Conference in 2019, and we re-connected the following year; we had enrolled in the same week-long seminar course. During this second encounter, I was given a peek into the vivid imagination of this quiet-spoken, thoughtful author when she read a draft story about a raccoon and a woman living in a barren landscape. Let me say some images will be stuck in my mind forever.

In late 2021, Rosaleen published a short story collection: Paper Demon. The title is apt. Demons are “forceful, fierce, or skillful performer[s], and that describes Rosaleen’s writing. Her stories push boundaries in relationships between partners, siblings and parents, and professionals; she provides an alternate take on disability culture and homelessness and a likely too true take on first-world-third-world encounters. If that were not enough, she confidently writes in magical realism and speculative fiction.

Rosaleen is a skilled disruptor of the ordinary. After each story, I set the book down and marvelled at her creativity and intellect. I look forward to her next collection, which I hope will contain the raccoon story. In the meantime, I will satisfy myself with re-readings of Paper Demon.

Fight Night by Miriam Toews

Fight Night is a story of hardship, heartache, resilience and hope, and it’s told from the perspective of a nine-year-old girl as she writes letters to her absent father. Her life is more than a tad chaotic: she has been expelled from school; her mother and grandmother’s relationship is fraught; family finances are tenuous, and she is anxiously awaiting the birth of her sibling. The span of the story is about four months. The ending is happy and unexpected.

I loved this book and will be re-reading it.

Night Swimming by Janet Turpin-Myers

I’ve come to Nightwimming (2013) belatedly. My only explanation is that I started reading Janet’s work with her next novel, The Last Year of Confusion, published in 2015.

I met Janet in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 2014, at my first Writer’s Union conference. Actually, it was my husband who met her first. He said, “You must meet Janet Turpin-Myers. She’s a bundle of energy, and she lives close to us.” I, however, was a shrinking violet; my anxiety was at a fever pitch. To paraphrase Alice Munro, “Who did I think I was?” to be attending a conference of REAL writers. I came from a nursing career where I wrote book chapters in management texts, conference presentations and scientific papers. That was technical writing, not REAL writing, and one novel didn’t make me feel like a full member of The Writers’ Union of Canada.

Since then, Janet and I have become friends, and yes, she still talks more than I do, but I think that’s because she thinks about writing all the time and wants to share her observations. (Have I said that she’s a REAL writer?)

Enough about me/us.

Night Swimming captured my imagination. It’s a story that can sweep the reader into the lazy, endless days of early teenage years spent with best friends at a summer cottage. It’s both a coming-of-age novel and a retrospective that explores friendships, romances, regrets, the hippie culture of the 60s and the moon landing. The writing is superb, poetic at times, and there is wordplay, i.e. to celebrate the moon landing, two spinster twins make “macamoons,” aka macaroons.

The structure of the book interested me, and as I came to each chapter, I would silently question what the author was doing with the chapter headings. All became clear at the end. And that’s why I have to re-read this book.

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles

This book came to me as a book club reading. I couldn’t obtain a copy in time for that meeting but was so absorbed by the discussion that I made a point of catching up. I’m so glad I did.

All That She Carried is a scholarly recreation of a cotton sack passed down through generations of a Black family. The author has woven history, economics, geography, religion, and culture into an account that reads like a novel, but it’s not one. Charleston, North Carolina, in the 1800s, and its society financed by slavery, is vividly portrayed as the author methodically traces the origin of the embroidered sack. Its journey started when Ashley’s mother, Rose, handed her the unadorned sack containing three handfuls of pecans, a tattered dress and a braid of Rose’s hair. As Rose gave Ashley the sack, she told her daughter that it was filled with love. Ashley, a nine-year-old girl, was on the auction block that day awaiting sale. The sack was ultimately embroidered by Rose’s great-granddaughter.

Imagine the anguish of seeing your nine-year-old daughter at a slave auction. The colonial behaviour that led to Black families being ripped apart by such auctions was the same mindset that tore First Nations children away from their homes (The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada). Family disruption in both instances was a strategic manoeuvre; it effectively destroyed any sense of cultural identity wherever it happened. Both books document what was tantamount to a system designed to brutalize bodies, destroy egos, and shred relationships

All That She Carried is a book that I hope has led me to greater compassion and wisdom. I’ll be recommending it to another book club of which I’m a member. And, yes, I will re-read it. (I borrowed this book, and because I forgot to photograph it before I returned it, I have no image to share.)

The two books that I’m currently juggling are Michael Pollan’s book, This Is Your Mind on Plants, and Alexander MacLeod’s Animal Person. I’m enjoying both. They’re fine writers.

Bonnie Lendrum is the author of Autumn’s Grace, the story of how one family manages the experience of palliative care with hope and humour despite sibling conflicts, generational pulls and career demands. Autumn’s Grace is a powerful commentary on the need for well-organized and well-funded palliative care in private homes and in residential hospices. It’s a gift to people who would like to be prepared as they help fulfill the final wishes of a family member or friend.

©2022, Bonnie L. Lendrum, All rights reserved.